This drawing I completed after visiting the Vermeer Milkmaid exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. What luck to be in the city while the Met had a special exhibit about Vermeer. I was able to study the paintings in real time, and try to understand what made them work.

This drawing I completed after visiting the Vermeer Milkmaid exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. What luck to be in the city while the Met had a special exhibit about Vermeer. I was able to study the paintings in real time, and try to understand what made them work.

I wish I could live in that museum (I loved From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler when I was a kid), but, alas, they will not let me. So whenever I visit New York, I spend as much time in the museum as possible, sketchbook in hand, trying to infuse my brain with master works. I don’t always understand what I’m learning while I’m at the museum, but somehow it ferments in my brain and bubbles to my conscious mind later.

One of the things that I noticed in Vermeer’s work was how he often framed the figure with geometric shapes. In A Woman Asleep, he frames the face of the young woman with a gray square. He often uses a wall hanging of a map as a geometric element that frames the subject—look at Young Woman with a Water Pitcher, Woman with a Lute, and Woman in Blue Reading a Letter. (Incidentally, if you’re interested in Vermeer, The Essential Vermeer is a terrific online resource.) But it really didn’t make a big dent in the attention I was paying to Vermeer’s color and brush technique.

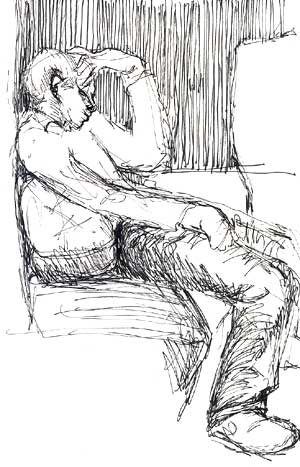

But I must have filed this bit of framing arcana on top of one of the piles of information cluttering my mind, because it surfaced later that evening. After a three hour stretch at the museum, I tiredly took the train back to New Jersey where we were staying. I sat across the aisle from this young man who was trying to sleep, and took out my sketchbook to capture his lanky pose.

Suddenly I realized that it wasn’t his face (I could scarcely see it), or his figure that attracted my attention, but rather, the way he was framed by the dark of the window and the back of the seat. Light bulbs went off in my mind. This was what Vermeer was talking about when he use a shape to frame his focal point!

It’s a simple sketch, but it pleases me because it reminds me that I’ve discovered a new way of seeing.