I’m relatively new to the sport of public painting, and I am sometimes surprised by people’s reactions when they watch me paint. Usually I get the standard “Oh, my mother, father, sister, brother paints. They’re really good.” But sometimes other emotions come bubbling to the surface, and I’m surprised by the intensity.

I’m relatively new to the sport of public painting, and I am sometimes surprised by people’s reactions when they watch me paint. Usually I get the standard “Oh, my mother, father, sister, brother paints. They’re really good.” But sometimes other emotions come bubbling to the surface, and I’m surprised by the intensity.

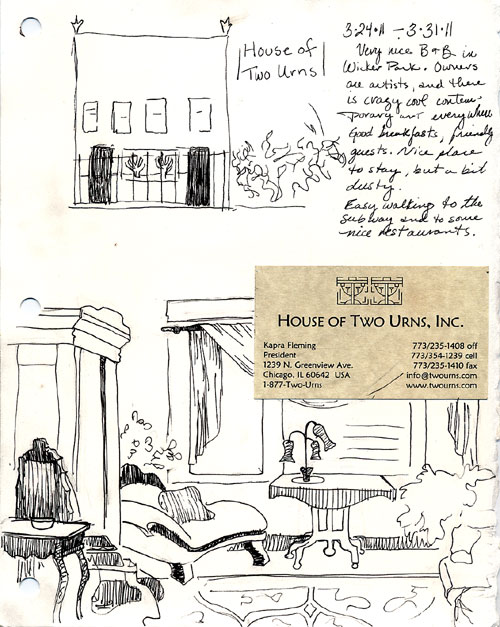

I made this pencil sketch at the museum restaurant (nothing but graphite in the museum, remember?), and that evening, while sitting in a crowded restaurant, I pulled out my gouache paints and watercolor brush and started adding paint.

The table where we sat was at a choke point in the floor plan; it slowed traffic considerably. The customers, intent on ordering tapas, didn’t pay much attention to my splashings, but the waiters did. They stopped briefly each time they passed our table to watch the progress of the color sketch, smiling and whispering to each other.

One young man was particularly interested. He asked several times, insistently, where and how I learned to do that. Then he asked if I taught classes.

“No, I don’t,” I answered. “But in Chicago there are tons of ateliers and schools.”

He grumped. “I tried a school for art once. There was to much book stuff for me. I don’t want to learn other people’s ideas, I want to do my own.”

¡Aye Chihuahua! Not like books? Not study other people’s ideas? That makes my mind reel about like a drunken turkey on Christmas eve.

I tried to keep my flabbergastment to myself, because I could see a flame in his eyes, and I didn’t want to extinguish it. I recognized that flame because I know that bit of fire. It burns inside your chest. It burns and it hurts, because you want to do something so much that you don’t even have words for it, you don’t know how to get there, and you’re afraid to even try.

A flame like that is easily blown out by the wrong word, a flippant remark, or indifference from another artist.

My step-daughter and I spent the rest of dinner searching our smart phones for Chicago ateliers and by the end of dinner, we had given him a list of ones that looked promising—schools that looked like they had solid programs in drawing and painting rather than a lot of theory and academics. At the end of the evening, we presented him with the list.

“Try these schools,” I advised. “I think they’ll teach you how to draw and paint. But I hope you look at art books. You’re studying art, so the books you’ll study are full of pictures. And that’s got to be a good thing, right?”

He hesitantly nodded, and took the scrap of journal paper I handed him and stuffed it in his wallet. I hope that strong blue flame I saw in him burns brightly enough to get him down to one of those art schools, do the work, and, yes, read some books.

If you think this blog might be of comfort to someone, please share it